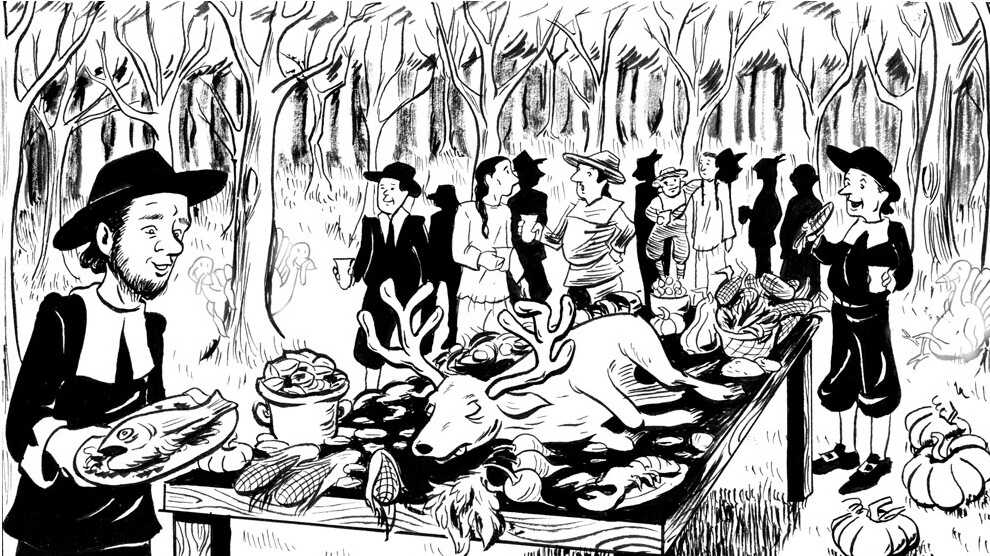

Real Men Eat Beef Turkey Cartoon

What theyreally had for dinner. Can you spot the 3 turkeys? They got away.

Allison Steinfeld

I did this last year. Here it is again, ever so slightly amended, in question/answer form.

How long was the first Thanksgiving dinner?

It wasn't just a dinner. It lasted three days.

Who was there?

About fifty Pilgrims came. Plus 90 Wampanoag Indians. Says the writer Andrew Beahrs: "About two of every three people there were Wampanoag." (Maybe that is why, in the middle of the party, the English took out their muskets and "exercised arms," which Beahrs says was probably target practice, their subtle way of saying, "Guess who's got the firepower here?")

Was it a family event? Were there ladies there?

Probably not. The only eyewitness account mentions "some 90 men." This was a political gathering. The Wampanoags and the Pilgrims were cementing a military alliance. Massoasoit, the Wampanoag king, was there. So was the English governor, William Bradford. The first Thanksgiving was mostly a guys-only event where the English women, says Beahrs "were likely doing the bulk of the cooking."

Was it held indoors? Around a big table?

No, the first Thanksgiving was probably held outdoors, including the meals. The English houses were too small to get everyone inside.

Did they eat turkey?

We don't think so. The Wampanoag guests brought five deer with them, so venison was on the menu. The English brought fowl, "probably migrating waterfowl like ducks and geese, which were plentiful in autumn," says Beahrs. "Governor William Bradford does mention taking turkeys that year, but not in connection to the harvest celebration."

How about cranberries?

Sorry. "If anyone at the gathering ate cranberries, it definitely wasn't as a sweet sauce," writes Beahrs. Sweet cranberries need maple syrup, an ingredient that wasn't plentiful till 60 years later. "The Wampanoag often ate the berries raw, or else in boiled or ash roasted corn cakes."

Sweet potatoes? Pumpkin pie? What else was on the table?

Pumpkins, maybe. But not pies. They wouldn't show up for another generation at least.

Linda Coombs, an Aquinnah Wampanoag and director of the Wampanoag Center for Bicultural History at Plimoth Plantation, guesses they ate "sobaheg," a Wampanoag favorite: a stewed mix of corn, roots, beans, squash and various meats. Plus the easy-to-gather local food: clams, lobsters, cod, eels, onions, turnips and greens from spinach to chard.

So how did turkey get to be the Thanksgiving bird?

Gradually.

Two hundred fifty years after the original Thanksgiving dinner, one of the hottest cookbooks in America, a collection of recipes from Ohio housewives called the Buckeye Cookerie, suggested a bunch of 'traditional' Thanksgiving dinners, and many of them, says Beahrs, ignored the turkey:

[Buckeye Cookerie] suggested oyster soup, boiled cod, corned beef, and roasted goose as good Thanksgiving choices, accompanied by brown bread, pork and beans, 'delicate cabbage,' doughnuts, 'superior biscuit,' ginger cakes, and an array of fruits. Chicken pies were a particular favorite and seem to have been served nearly as often as turkey (usually as an additional dish rather than a substitute).

Who put the turkey on top?

Abe Lincoln helped by declaring Thanksgiving a national holiday. I'm sure the turkey and cranberry industries helped too, but Beahrs gives his biggest props to a 19th century magazine editor named Sarah Josepha Hale. She and her magazine, Godey's Lady's Book, campaigned for a national day, wrote letters to governors, to every member of Congress, even to the president, and when she wasn't lobbying, she was writing novels that romanticized turkeys in that over-the-top drooling-with-her-pen way that may make you laugh ... but it worked. Here's a passage from her 1827 novel, Northwood:

The roasted turkey took precedence on this occasion, being placed at the head of the table; and well did it become its lordly station, sending forth the rich odor of its savory stuffing, and finely covered with the froth of its basting. At the foot of the board, a sirloin of beef, flanked on either side by a leg of pork and loin of mutton, seemed placed as a bastion to defend the innumerable bowls of gravy and plates of vegetables disposed in that quarter. A goose and pair of ducklings occupied side stations on the table; the middle being graced, as it always is on such occasions, by the rich burgomaster of the provisions, called a chicken pie.

That's turkey, then sirloin, then pork, then lamb, then goose, then duck, then chicken pie, all in one sitting! Did they eat small portions or just explode? I don't know, but notice, by 1827, chicken pie, once in contention, has been shoved to the end of the table. It took 300 years or so, but eventually the turkey knocked off every other contender and is now center stage, by itself, gloriously supreme, stuffed, adorned, triumphant. Viva la turkey!

Andrew Beahrs' book celebrating America's vanishing wild foods is called Twain's Feast, Searching for America's Lost Foods in the Footsteps of Samuel Clemens (Penguin Press, 2010). Thanks to artist Allison Steinfeld for her rendering of the first dinner. She's included three invisible (well, barely visible) turkeys who, she says, "got away."

buchananthersom2002.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.npr.org/sections/krulwich/2010/11/22/131516586/who-brought-the-turkey-the-truth-about-the-first-thanksgiving

0 Response to "Real Men Eat Beef Turkey Cartoon"

Publicar un comentario